When the first white settlers traveled west to present-day Bloomington, they found a hilly, wooded terrain far from navigable waterways and with minimal prospects for settlement.

“800 Seasons: Change and Continuity in Bloomington, 1818-2018,” a current exhibition at Indiana University’s Mathers Museum of World Cultures, tells the story of how Bloomington came into being through the voices of individuals over time. Building around the themes of land, water, food, transport, and shelter, the exhibit challenges present-day Hoosiers to reexamine the city and the people who made it what it is today. “It’s about recognizing the ground beneath your feet,” said IU History Professor Eric Sandweiss.

Through oral histories, images, and artifacts, the exhibit examines how people have thought about and shaped the land in the past and how the legacy of human settlement and expansion reverberates to the present day. “800 Seasons” is on display through Spring 2020.

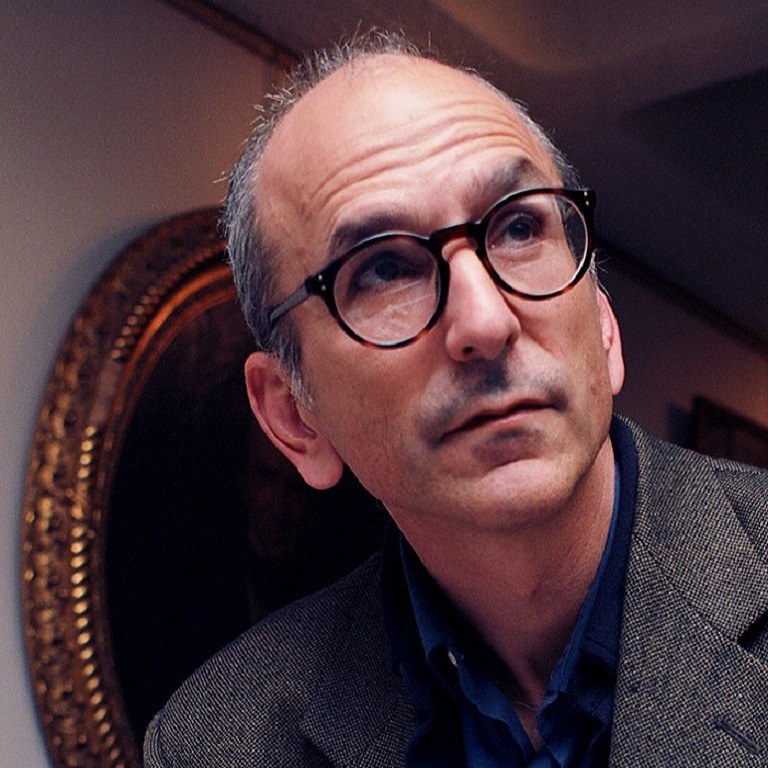

Sandweiss, who curated the exhibition, spoke with the ERI Explainer about the major concerns Bloomington residents faced in the early days of settlement and how American thought on the environment has evolved over time.

Explainer: What was the inspiration for this exhibit?

Sandweiss: The colliding bicentennials of Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana, and IU were popping up, and I wanted some way to recognize those in an original fashion and to link them to environmental change.

Though we’re seeing changes in nature today that we haven’t seen before, whatever we face in the future is going to echo the past in some way. We thought it would be useful for us to track how environmental change has shaped Bloomington and to show people how our landscape is always changing.

Explainer: How did you go about your research and what themes did you find as you started digging into the environmental history of the area?

Sandweiss: As a historian, I approach my research with questions that lead to sources and places that I couldn't necessarily have planned.

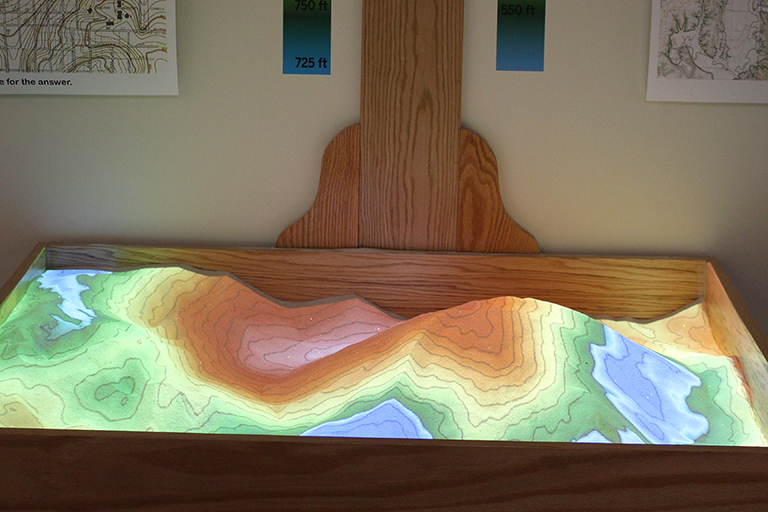

The big sense that I had entering this project was that I wanted exhibition visitors to understand the ground beneath their feet--to understand the history that is, literally, in place as they walk around the city of Bloomington. It’s a history of land, water, resources, and food—all of these really basic parameters or scaffolding for human lives that we take for granted or that we render invisible.

The work led me to individual voices throughout time, talking about how they viewed this place in the past, and a whole lot of primary sources, by which I mean oral histories that have been made and collected by the Monroe County History Center, the IU Center for the Study of History and Memory, and the Monroe County Public Library. I let those voices do the talking, and from there found the artifacts, the objects, and images to make their story real, whether it was someone from 1820 or 1950.

Explainer: You mentioned the themes of land, water, and food. As white settlers came into the area 200 years ago, how did people’s relationship to these necessities evolve?

Sandweiss: A few things emerge as the big story lines. First, we were able to show how close in time and place we are to people who really thought that this was their home and didn't need or want to leave. Native Americans had a presence in Monroe County even into the 1820s. There's a big treaty in 1818 that enforces white presence in Monroe County and helps the city get settled.

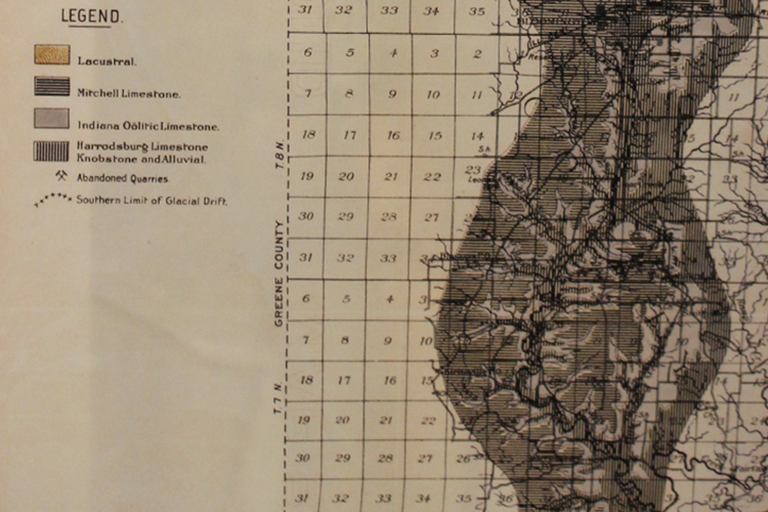

The second thing we looked at was the ground beneath our feet. We tried to show how essential the geological formation of the city and county is to recent history. The obvious story here is limestone, which becomes a source of economic opportunity by the 19th century and into our own time.

That story bleeds into another section of the exhibit, which is water. The search for water is a story Bloomingtonians come back to again and again. The fact that limestone is so porous and does not hold water meant that any time people tried to pool water and create reservoirs, they were constantly foiled. You couldn't have industry, you couldn't have extensive settlement. People were digging wells hundreds of feet deep, and that was expensive. You almost couldn't have a university. IU trustees threatened to leave here more than once, mostly over the water issues. Ultimately people started listening to the expert geologists at IU and in the state government. That led to building in a sandstone zone instead of a limestone zone, which later became the sites for Lake Griffey, Lake Lemon, the University Reservoir, and then finally Lake Monroe in the 1960s.

Explainer: In your research, how did humanity’s relationship with nature change and did individuals' descriptions of nature change over time?

Sandweiss: There's plenty of talk, or at least lip service to, the beauties of nature and the wonders of the natural world. You get the usual kinds of tributes to lovely countryside in the 1800s, but it's always conditioned by, “Can you make a living? How is it going to be for farming?” The land becomes something to tame, to conquer, to regularize, to regulate.

Now, of course, we're at a new stage where we recognize that making the environment work for us often makes it not work someplace else. There has to be some kind of greater symbiosis between what people think they can get done in the city and what resources are available to them. I think you can see some of the traces of that change over time, but definitely most of the story is about human ingenuity, the power of positive thinking, and the idea that somehow we can turn this land into an engine of prosperity.

Explainer: As the exhibition transitions to more modern times and the adverse consequences of neglecting our relationship with the natural world becomes more pronounced, do you see a new strain of thought emerging?

Sandweiss: I think the short answer is yes. We tried to turn the exhibit back toward the contemporary visitor and to the subject of modern Bloomington. We tell the stories of people who are involved in different facets of food, water, work, labor, and transport. We interviewed people who are around today talking about their efforts to come to grips with the same issues as people in the past.

In profiling just a handful of these people, what we're really trying to do is to tell the bigger story of this ongoing adjustment to the challenges, the realities, the demands of strained resources with continued growth and the effort that is required to feed a population that is not equally enabled with wealth.

All of those issues, I think, require complex thinking. It'd be vain to say that we are better complex thinkers today than we were 100 years ago, but at least we can crack into the minds of some of the best people doing it today and get their take on how the mesh of environment, political, and social community fits together—and how best to make it sustain.