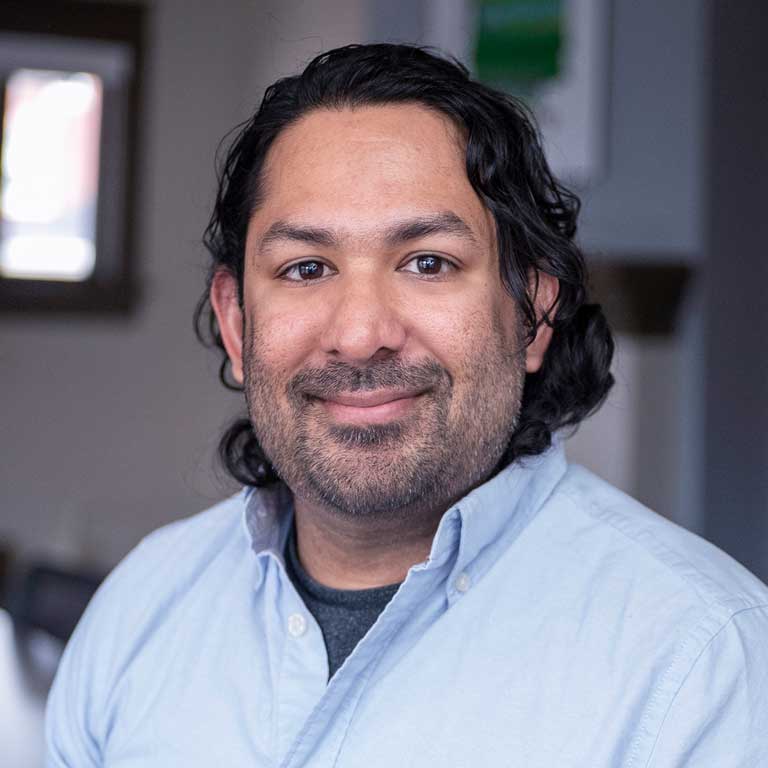

A new study co-authored by Environmental Resilience Institute Research Fellow Ranjan Muthukrishnan describes why an invasive seagrass pushing its way into United States coastal waters is spreading so fast.

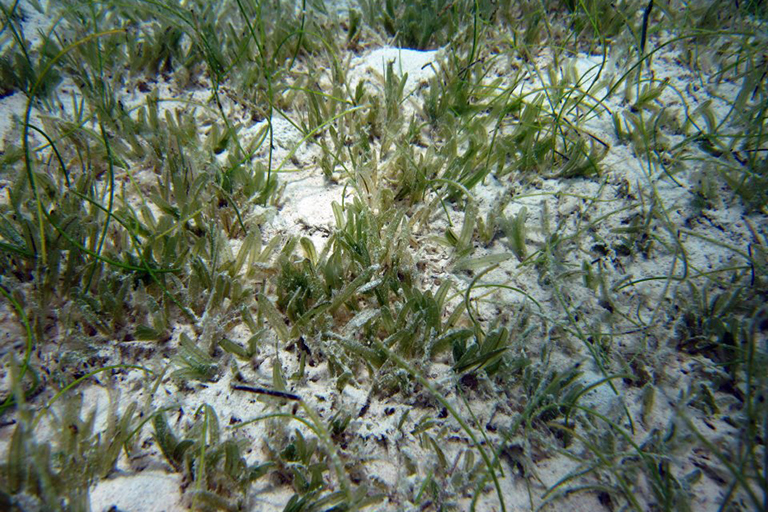

Halophila stipulacea (H. stipulacea), a seagrass native to the Indian Ocean, has recently established itself in Caribbean water. To better understand the aggressive growth and spread of H. stipulacea, Muthukrishnan and his colleagues conducted field work within Virgin Islands National Park, removing the seagrass from several plots on the ocean floor and monitoring its growth and recovery.

After 14 weeks of monitoring, the researchers found H. stipulacea had regained approximately half of its original cover. Based on these observations, the team predicted that the invasive seagrass could return to its original levels in as few as 17 weeks. The study, published online, will appear in the February 2020 edition of the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

“Halophila stipulacea tends to be quite short in stature, but it grows fast and thick, crowding out native seagrasses,” said Muthukrishnan, ERI’s Invasive Species Ecology Fellow. “It’s really important that we evaluate the impact of this invasive species and how it is changing the local environment.”

Native seagrasses play an important role in supporting a wide range of Caribbean aquatic species, including fish, snails, crabs, and sea turtles. When H. stipulacea displaces native seagrasses it can destabilize established relationships between plants and animals. For example, the H. stipulacea invasion has forced green sea turtles to forage further afield for their preferred food source, the native seagrass Thalassia testudinum, which is more nutritious than H. stipulacea.

Though the invasive seagrass is expanding its footprint on the Caribbean ocean floor, Muthukrishnan said government officials can implement policies that can help manage H. stipulacea’s spread, such as encouraging boaters to use mooring buoys instead of anchors, which disturb plant life on the ocean floor, and to clean fishing gear before changing locations so that the H. stipulacea is not transported to new areas.

“Prevention is far more important than any cure because it’s really hard to remove after the fact,” Muthukrishnan said.