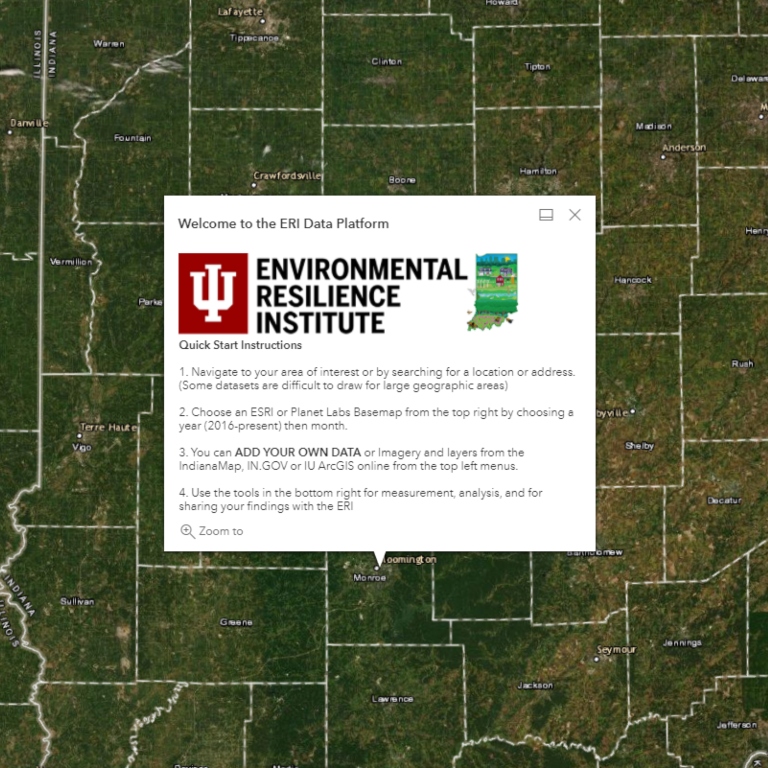

Indiana University’s Environmental Resilience Institute (ERI) hosted its biannual data summit on May 21 to share affiliated researchers’ new research and tools. The summit included presentations on urban green infrastructure, how the pandemic has influenced Hoosiers’ attitudes on climate change, how farmers think about resilience, and an overview of the ERI Data Platform.

“From the beginning, environmental data has been a cornerstone of ERI’s mission to help Indiana address environmental change,” said Gabe Filippelli, ERI’s executive director. “The research and data presented at this spring’s summit showcased the myriad ways information can be applied to make decisions when tackling issues related to climate change in Indiana, such as city planning and farm management.”

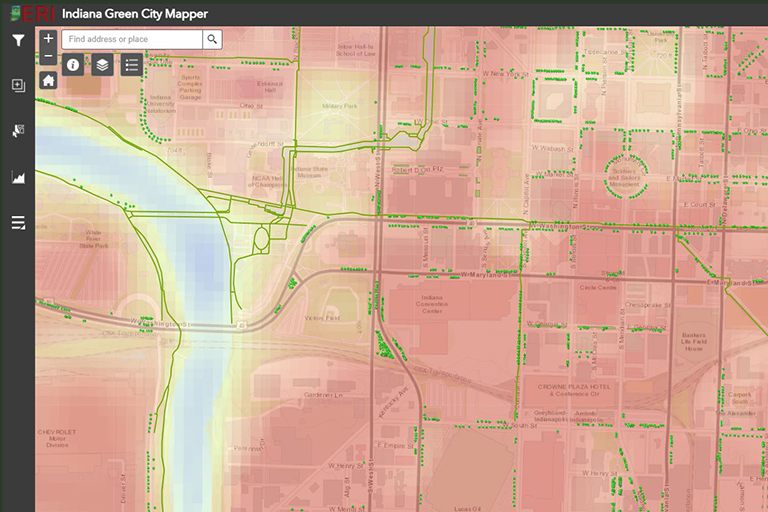

Kicking off the summit, Hannah Gregory, an ERI research associate, discussed the new Indiana Green City Mapper (IGCM), a statewide spatial inventory that tracks six forms of green infrastructure—urban forests, green roofs, parks, greenways and trails, urban food gardens, and green stormwater infrastructure—and pairs this information with socioeconomic and climate change-related data to help inform resilience planning.