Since 2017, science teachers from Indiana and beyond have been attending Educating for Environmental Change (EfEC) to get ideas on how to effectively teach environmental science and climate change in the classroom. With this year’s program being held online for the second year in a row, teachers from across the county virtually flocked to Indiana University’s Bloomington campus to deepen their understanding of key concepts related to environmental change.

Thirty-nine middle and high school teachers from 11 states—and one from Tajikistan—attended the workshop, held June 14 through June 16, to learn about lessons, resources, and activities they can use in the classroom to teach students about the causes, consequences, and mitigation of environmental change. IU faculty, many of them affiliated with Indiana University’s Environmental Resilience Institute, together with veteran science teachers led each of the sessions.

"Committing to teaching about climate change often requires complex and nuanced work: How do you help students explore a science topic that is so highly politicized yet drives much of our current news cycle? How can you help students see both the big picture and the staggering quantity of data that informs it? And how can you balance the severity and urgency of the problem with hope, with agency, and with action?” said Kirstin Milks, a science teacher at Bloomington High School South and one of the leaders of the workshop. “Educating for Environmental Change provides a rich space for classroom teachers to explore these questions with input from scientists, scholars, and educators from formal and informal settings."

Each day of the workshop centered on one of three essential environmental change topics:

- how we know the climate is changing and that humans are accelerating it,

- what the impacts of climate change are,

- and what can be done to mitigate the severity and impacts of climate change.

To encourage engagement and work around some of the limitations of virtual workshops, the days were divided up between lessons, activities, and small group “breakout rooms.” In several sessions, workshop leaders demonstrated age-appropriate activities for the classroom and then sent the teachers outside to practice themselves.

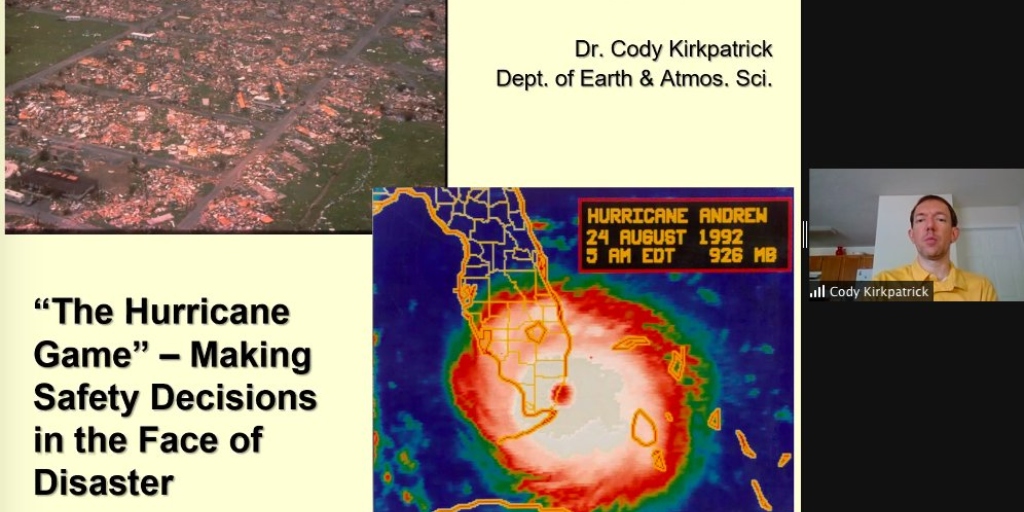

The workshop also introduced group activities to the teachers that covered key concepts, such as how scientists study climate change, how students can learn like a scientist, and what we can do about climate change and its impacts. One demonstration led by Cody Kirkpatrick, a senior lecturer in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, focused on decision-making and information constraints during a hurricane. Playing the part of the students, the teachers made decisions on how to act based on real hurricane data. At the end, they reflected on how the activity relates to real disasters and how under-resourced communities have a much harder time preparing for disasters—an important parallel to how countries must set climate-preparedness policy and slow global climate change.

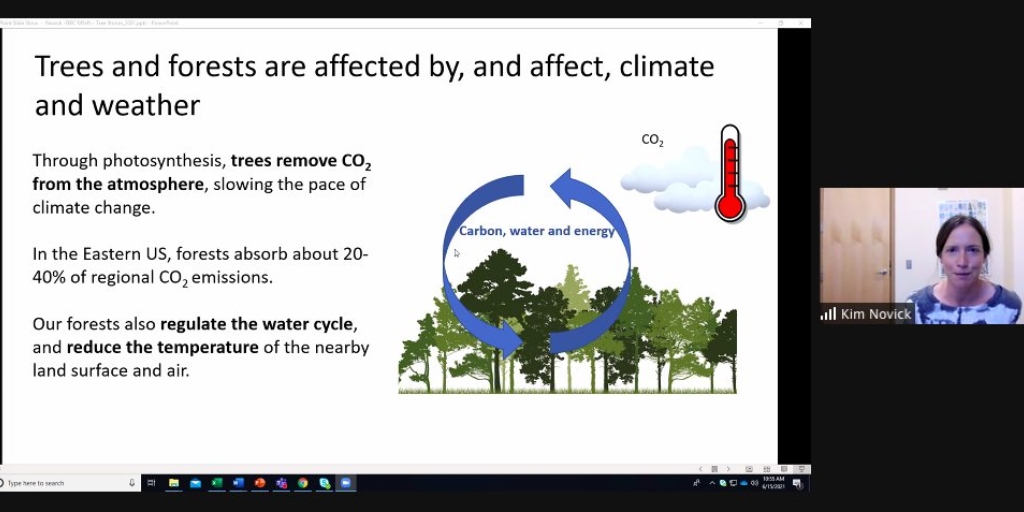

In another group activity, Kim Novick, an associate professor in the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, explored how trees and forests interact with weather and climate. The presentation focused on how the timing of tree’s annual rhythms can help track climate change and the positive impacts trees have on the climate and ecosystem health. Novick provided the teachers tree identification cards and flash cards for classroom activities on tree identification. The teachers were then given time to go outside to try out the tree identification tools on their own as an example of how students can connect the science of their local environment to climate.

At the conclusion of the workshop, the participating teachers reflected on the ideas they plan on applying in their classrooms.

“This experience allowed me to gain personal knowledge and valuable insight towards the learning of my students on the topic of climate change with an emphasis on science literacy,” said Katie Urcuioli, a science teacher at William Henry Harrison High School in West Lafayette, Ind. “I came away excited to implement multiple methods and resources to involve my students in authentic scientific processes and thought on a critically important issue.”

“While it would have been amazing to have the workshop in person, the virtual platform allowed for educators to participate from all around the world and made for a large and diverse group of participants and faculty,” said Matthew Aschaffenburg, a science teacher at Carmel High School in Carmel, Ind. “Thanks to the program, I now have a number of ways that I can incorporate climate change into my classroom through new topics to discuss, lesson plans, and activities to utilize.”