On Aug. 23, with temperatures soaring above 90 degrees throughout Indiana, local government staff and volunteers in Clarksville and Richmond, including seniors and school-age children, set out by bike and by car with an unusual goal in mind: gathering local temperature data.

The efforts are part of a project to map local hot spots in each community and better understand which areas are most impacted by extreme heat. Both Clarksville and Richmond, are part of the Beat the Heat program, led by Indiana University's Environmental Resilience Institute with funding from the Indiana Office of Community and Rural Affairs.

Through the program, each community hired a full-time heat relief coordinator to work with community stakeholders and develop a long-term plan to protect residents against the negative health impacts of extreme heat. The program also connected each community to resources, such as the community heat mapping campaigns coordinated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and CAPA Strategies.

"This was a true citizen-science project that was all about the community collecting their own local temperature data which will be used to better understand their heat exposure and their resilience to extreme heat," said Dana Habeeb, an assistant professor at IU's Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering and the program's principal investigator. "This data is essential for us to target policies and resources to those in our communities who are most impacted by extreme heat; with better targeting we can save more lives."

At three points during the day—morning, afternoon, and evening—the volunteers traveled pre-planned routes with temperature monitoring devices. The temperature data and photos collected by volunteers will be used to create high-resolution, color-coded heat maps that display localized temperatures at different times of the day.

“I was joking with my volunteers that it was a bad day to exist as a person, but it was a great day to exist as a data collector,” said Lucy Mellen, the City of Richmond’s heat relief coordinator, referencing the day’s steamy conditions.

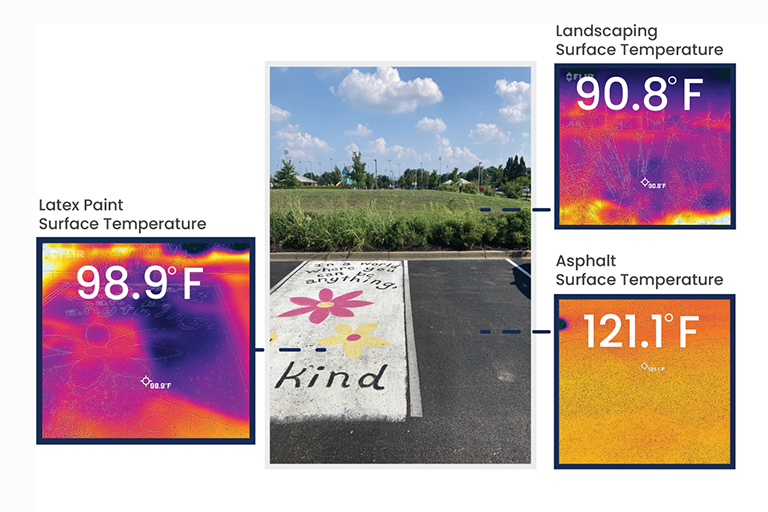

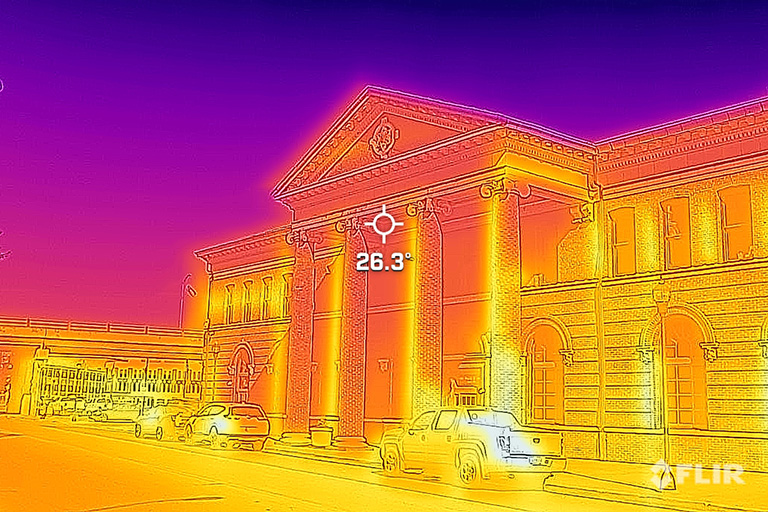

Some volunteers collected infrared photos of various surfaces around both cities to capture how heat impacts everyday spaces at different times of the day.

“Being able to see the surface temperatures change across different materials across the city, like local parks, play equipment, concrete, and grass was really interesting,” said Town of Clarksville Heat Relief Coordinator Bronte Murrell. “The temperature changes between these surfaces were dramatic and we were excited to see how extreme heat is experienced in our community.”

Hoosiers are already experiencing growth in the frequency of extreme heat events due to climate change. Indiana’s average annual temperature has risen 1.2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1895 and temperatures are projected to rise even further by mid-century, according to the Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment.

This trend contributes to the length and severity of heat waves experienced by Hoosiers. For example, Richmond currently experiences 18 extreme heat events each year. An extreme heat event refers to a 24-hour period where temperatures exceed 90 degrees during the day or do not fall below 68 degrees at night. “By 2050, if we don’t limit our greenhouse gas emissions, we could be seeing up to 74 of these events every year,” Mellen said.

Residents of Clarksville currently experience 42 extreme heat events each year. Without drastic global action to curtail climate change, they could see that number balloon to 103 days.

There are many steps communities can take, however, to offset and become more resilient to high temperatures, including adopting a tree canopy ordinance, assessing the need for cooling centers, and identifying opportunities to build infrastructure (i.e. roads and bridges) that can withstand a wide range of temperatures.

Murrell said Indiana communities who are just starting to plan for the impacts of extreme heat should start by talking to a diverse group of community stakeholders.

“Talk with your hospital. Talk with your public health department to see how this issue affects people,” Murrell said. “But, it is important to not just talk to professionals. Talk to those who are most vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat—children, seniors, pregnant women, people with health conditions, communities of color, and others who may not have equal access to air conditioning. These are the people who are disproportionately impacted by summer heat.”

Hoosier communities who are not a part of the program can still take action to prepare for a future with more extreme heat.

“It is important for communities to plan now for extreme heat, even if they don’t think they are at risk at this moment,” Habeeb said. “Planning allows them to be prepared to respond immediately during a heat crisis and there are a lot of different policies and adaptation strategies that communities can employ for both mitigation and adaptation for extreme heat.”

About the Environmental Resilience Institute

Indiana University's Environmental Resilience Institute brings together a coalition of university scholars and leaders in the government, business, nonprofit, and community sectors to help Indiana better prepare for the challenges that environmental changes bring to Hoosiers' economy, health and livelihood.