They called it “The Life Line of Indiana”: over 600 miles of steel rail that linked the banks of the Ohio River to the shores of Lake Michigan. From its beginnings in 1847 until its demise amidst the corporate mergers of the 1970s, the Monon Railroad connected the upland South to the Midwestern industrial belt. Its trains carried stone, timber, coal, and—not least—people from one end of the state to the other, tying together Indiana’s varied cultural and physical regions through their shared connection to this uniquely Hoosier institution.

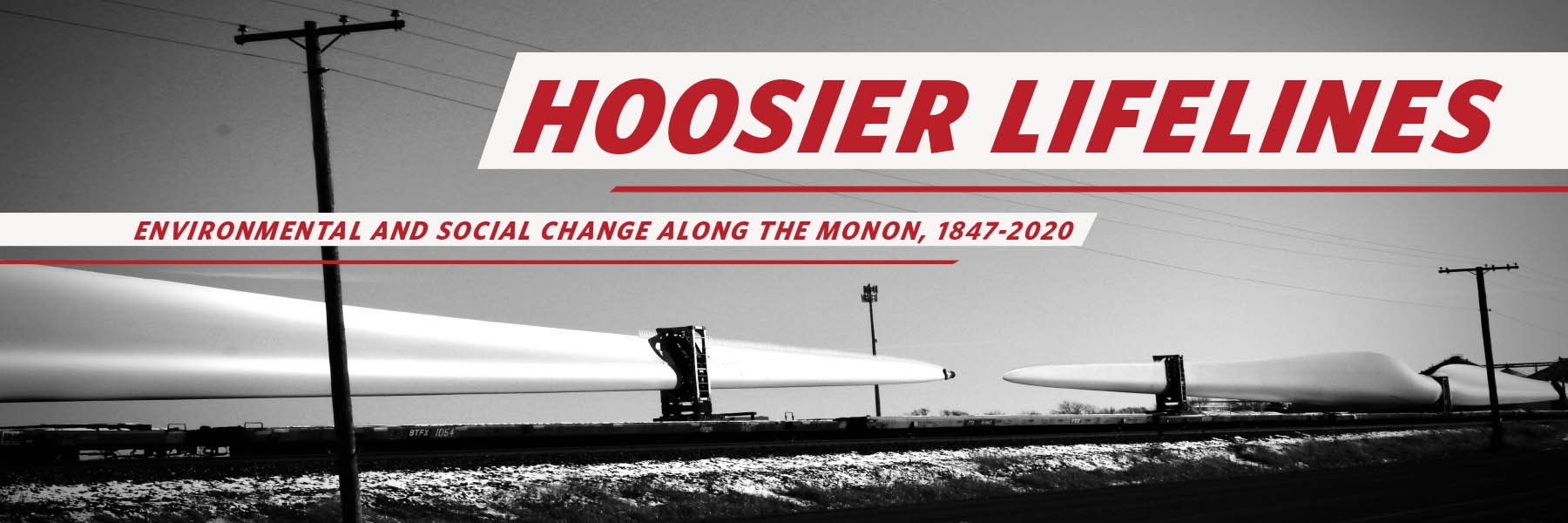

Hoosier Lifelines was an artistic and historical exhibition that debuted in 2021 and followed the historic Monon route. This imaginative exploration of Indiana’s changing landscape used the remains of the old Monon line—much of which today lies abandoned in the landscape between these cities—as the foundation on which to build a new understanding of the interplay of local landscapes, ecosystems, and social communities across time and space. During a time of environmental change, public health threats, and economic uncertainty, the exhibit prompted viewers to return to Indiana’s “Life Line” to ask: What will replace the energy-intensive network of industry and labor that once brought our state together? What will sustain our communities in a time of diminishing resources and accelerating environmental change?