A new study co-authored by ERI affiliates John Baeten and Rebecca Lave describes a novel mapping technique used by the researchers to reconstruct and analyze the Lower Wabash River floodplain. The results better capture how human activity has altered the river dating back to 1914 and can be applied to help restore wetlands or other ecological features.

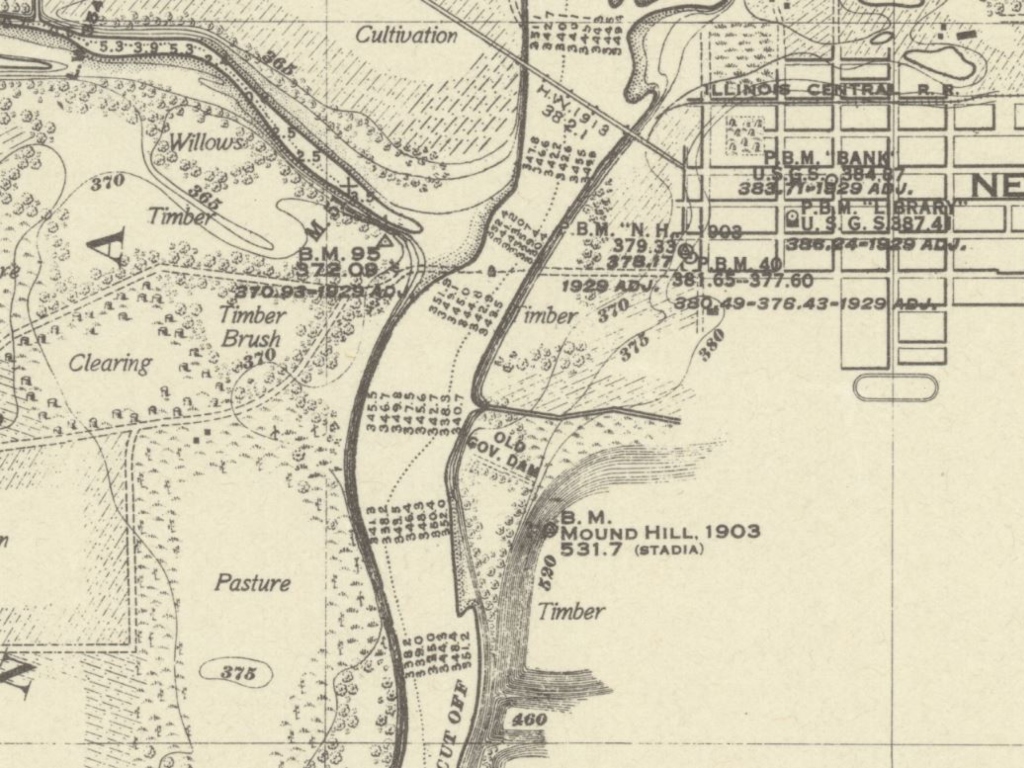

To better understand how humans have changed the land around the Lower Wabash River over the past 100 years, Baeten and Lave worked with the IU Map Library to acquire historical survey maps of the area produced by the Army Corps of Engineers. They then digitally reconstructed these maps in a Historical Geographic Information System (HGIS), using a drawing tablet and stylus to digitize the environmental features.

“Using the drawing tablet and stylus instead of the traditional use of a mouse allowed us to have a higher degree of precision for digitizing environmental features over extensive scales, such as rivers,” said John Baeten, an IU postdoctoral researcher and Director of the Historical Landscapes Laboratory. “Using a mouse to digitize features works well for uniform features, like buildings, but for more irregular features like rivers and swamps, the built-in tools within a GIS are really limiting. Using a drawing tablet and stylus is not only a creative way to digitize features, but it allows us to digitize features faster and more precisely.”

Baeten and Lave also analyzed data from the National Land Cover Dataset (NLCD) and the National Hydrography Database (NHD) to understand how the Lower Wabash River has evolved from what was observed on the 1914 maps.

Comparing the data revealed substantial changes to the river over time, including an 80 percent reduction of wetlands and swamps, a 27 percent increase in new ditch lines, and the removal of 87 percent of sandbars from the Wabash channel. These changes are the result of attempts to make the river more navigable, increasing the agricultural capacity of the land, and reducing the breeding grounds of mosquitoes. In both the past and present, agriculture was the dominant land use feature on the landscape, accounting for about two-thirds of the total study area.

The historical comparison provides a baseline for the landscape that can be used for various activities, such as restoring wetlands for flood control and nutrient retention purposes.

“If you don’t know what the land used to be like, and how it used to function, you won’t be able to restore it as effectively,” Baeten said. “Using this information, a farmer can see how their land used to appear and where they can implement strategies to make their farm more resilient to environmental impacts like agricultural runoff, which is impacted by ditches, and flooding, which can be reduced by restoring wetlands or similar features.”

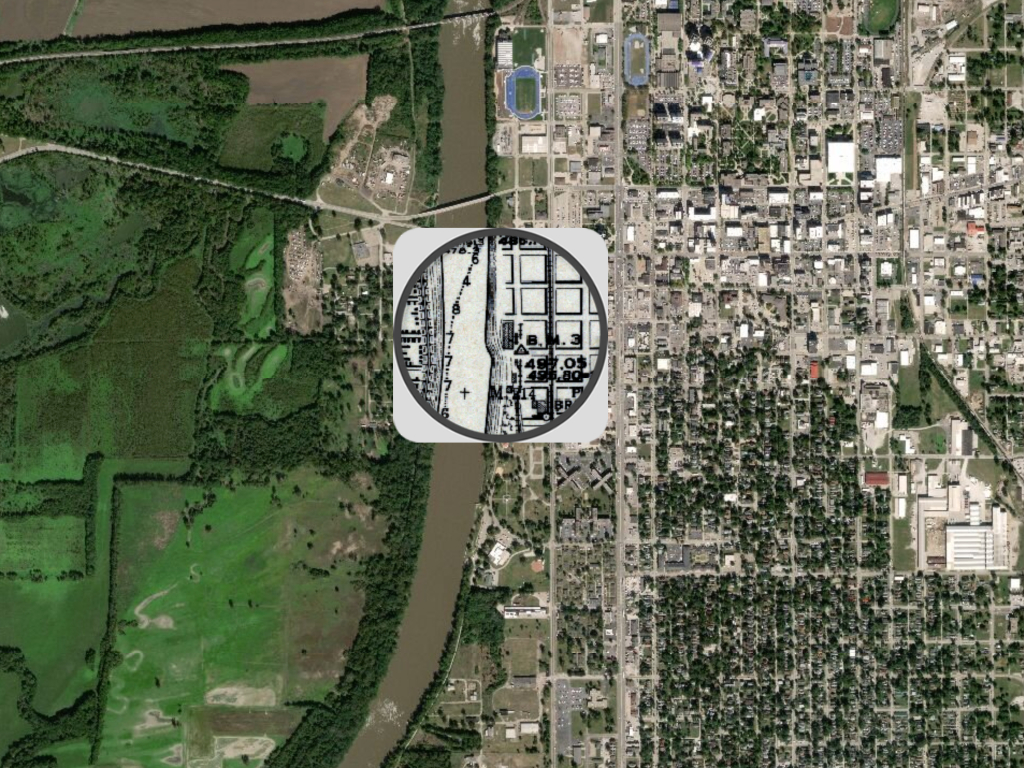

To allow others’ to see the extensive changes for themselves, the team created a story map where users can compare past survey maps to satellite images of today.

The information from this analysis will be made accessible to the public in the future as more data is available.