As cities across the country grapple with systemic racial inequity during a hot summer of civil unrest, calls for racial and environmental justice have gained momentum in places like Central Indiana, where 4 in 10 Black residents live in neighborhoods with high air-pollution risk.

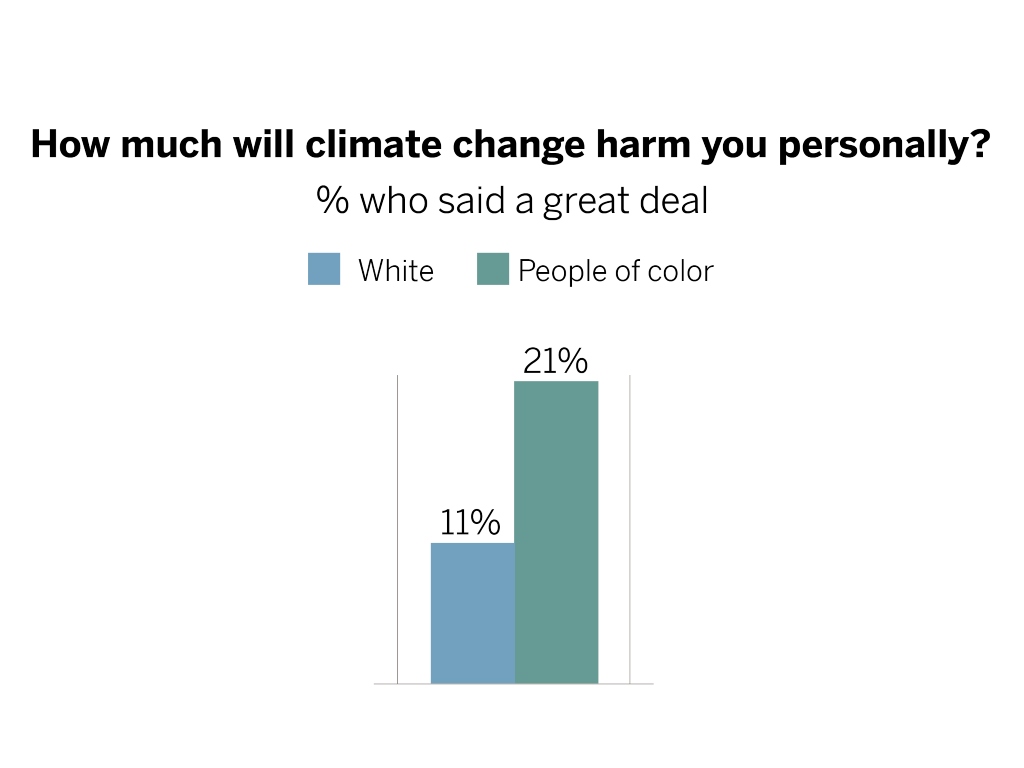

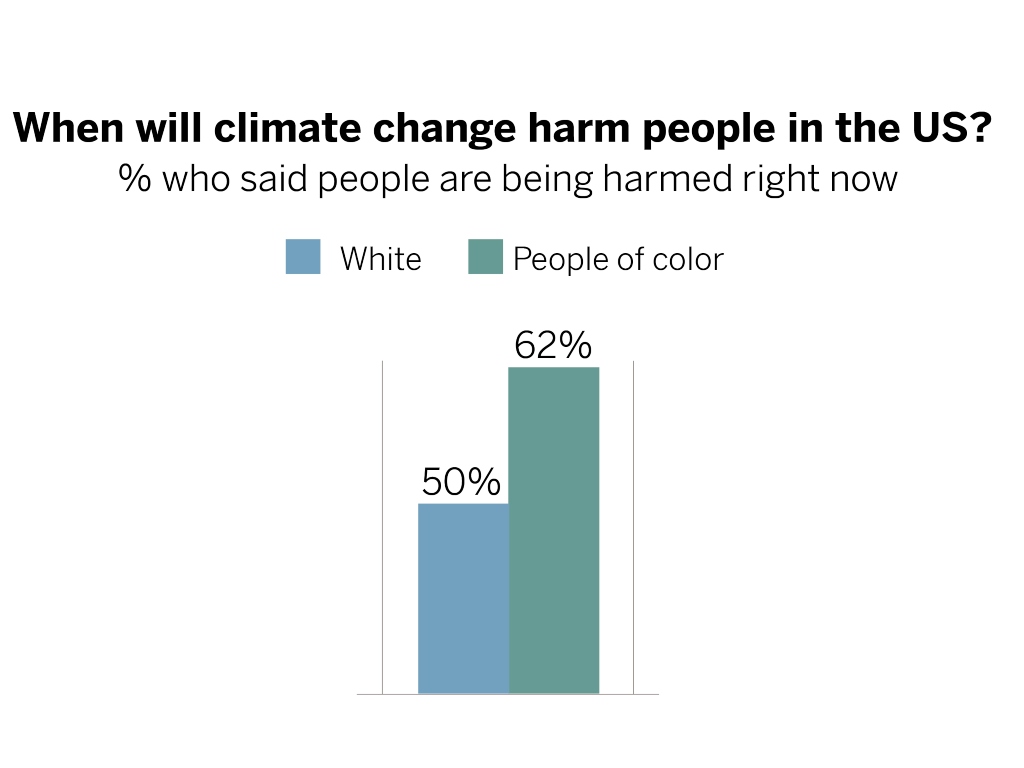

Findings from the Hoosier Life Survey, a statewide survey on environmental attitudes conducted by Indiana University's Environmental Resilience Institute, show that race also plays a role in Hoosiers' perceptions and vulnerabilities to climate change. According to the survey, in Indiana, people of color are twice as likely as white people to agree that climate change will harm them a great deal and 25 percent more likely to agree that climate change is harming people in the US right now.

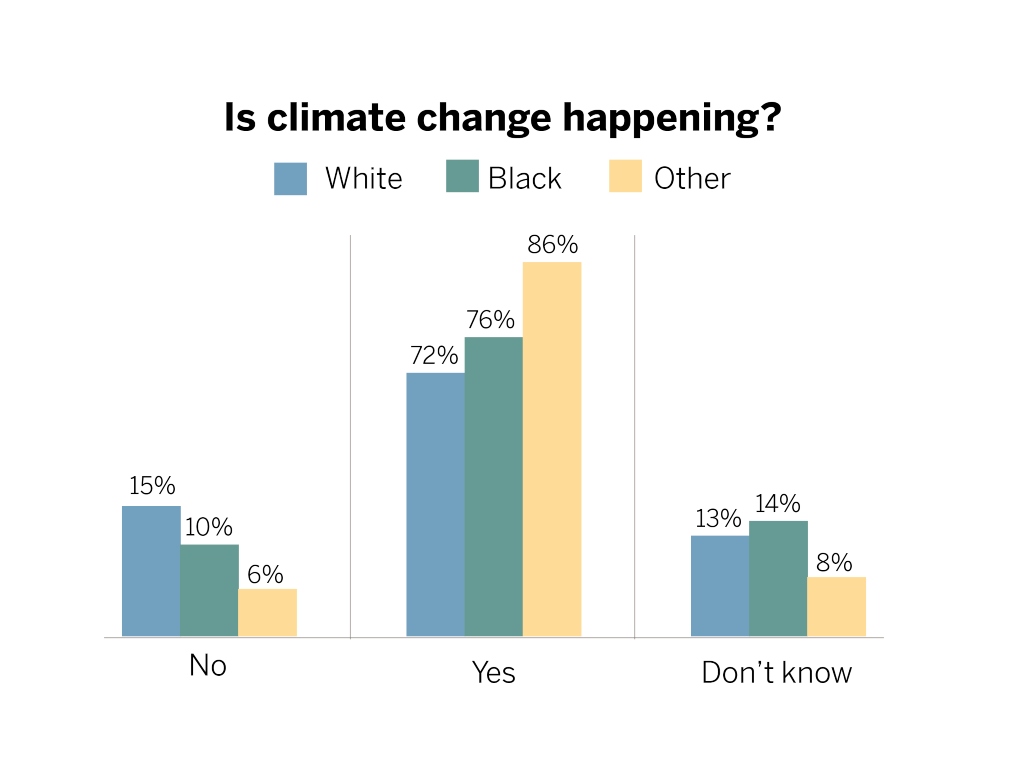

Additionally, Hoosiers of color are more likely to recognize that climate change is happening. Seventy-six percent of Black Hoosiers and 86 percent of non-Black people of color agree that climate change is happening compared to 72 percent of white Hoosiers.

“These survey results illustrate the importance of considering racial inequalities in climate resilience planning and resource allocation,” said Matt Houser, an IU sociologist and Environmental Resilience Institute research fellow who co-led the survey. “They also point to the willingness of minority populations in Indiana to support climate preparedness policy.”

As Hoosiers endure another hot and humid summer, differences in climate change perceptions between white and minority groups could be linked to differences in how Hoosiers experience climate change impacts, such as high heat days. The number of Indiana days with temperatures 95°F or higher has increased over the last century and is projected to increase more in the coming decades. More high heat days mean more heat-related illness and death.

These impacts, however, are not borne equally by all Indiana residents. Minority and low-income Americans are at higher risk of being affected by climate change impacts like high heat. They are also more likely to live near environmental pollution and to have less capacity to prepare for and cope with extreme weather and climate-related events. These social conditions cause a variety of adverse health outcomes, leading to more severe cases of COVID-19 among Black people in cities like Indianapolis, while also increasing the vulnerability of individuals and communities of color to climate change.

“We know from others’ research that Black Americans are especially vulnerable to the risks of high heat compared to other groups,” Houser said. “Black people are more likely to live in ‘urban heat islands’ where temperatures are magnified, and according to our and other survey results, Black people and other minorities are also less likely to have access to air conditioning.”

“These differences may partially explain why people of color seem more concerned about climate change than white people in Indiana. They may also explain Black Hoosiers’ greater support for community policies that help Indiana residents cope with heat.”

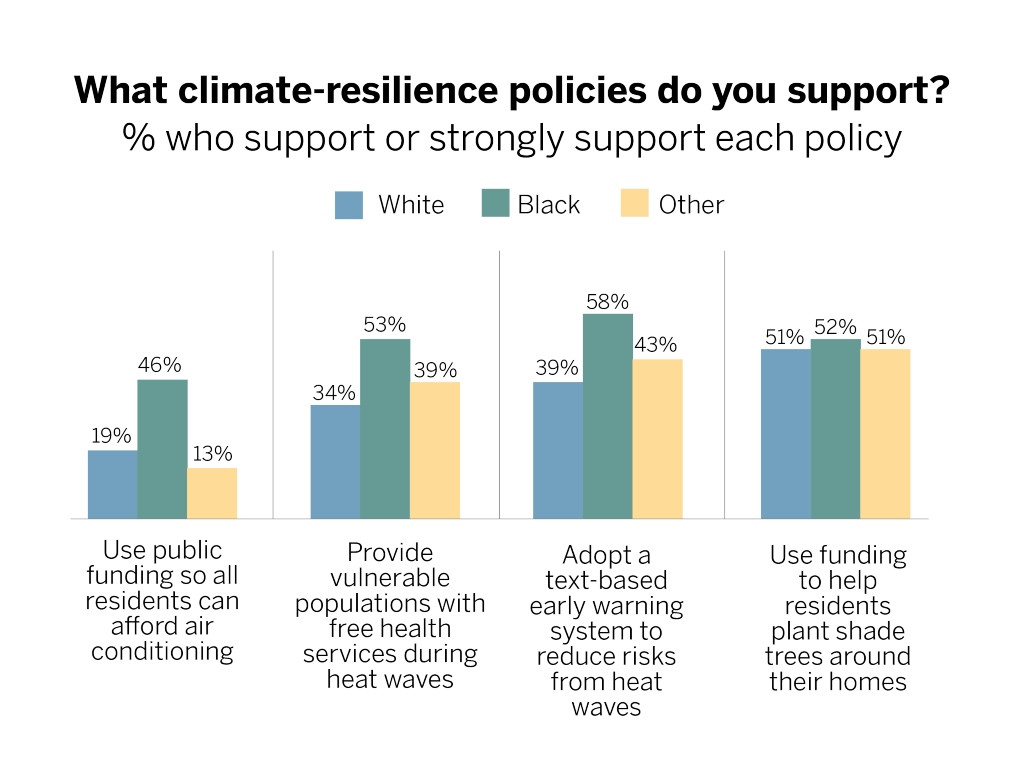

When asked about specific climate-related policies, Black Hoosiers were about twice as likely as white Hoosiers to endorse policies such as public funding for air conditioning, free health services for vulnerable populations during heat waves, and a text-based early warning system to reduce heat-wave risks.