Indiana University researchers are using a specially equipped drone this summer to better understand how two dam failures in Michigan drastically altered the local landscape.

In May 2020, floodwaters overwhelmed dams near Edenville, Mich. and Sanford, Mich., resulting in the displacement of 10,000 residents and over $200 million in property damage. Increased precipitation from climate change and aging US infrastructure threaten to make dam failures more common in the future.

Flying a drone equipped with an integrated lidar camera that uses laser light to measure the surface, IU Earth and Atmospheric Sciences (EAS) researchers Doug Edmonds and Brian Yanites, graduate student Harrison Martin, and pilot Steve Scott, are capturing short- and long-term changes to the Tittabawassee River and surrounding floodplain.

The research is being funded by the National Science Foundation through a Rapid Response Research grant reserved for projects that require timely data collection. Only a handful of such NSF grants are awarded each year.

Drone data gathered by the IU team is being shared widely with collaborating universities and civil engineers, and government agencies who are also studying the site of the disaster. The IU research team originally purchased the drone in 2018 using funds partially provided by Indiana University’s Environmental Resilience Institute, College of Arts and Sciences, and the Office of Vice President of Research.

“Traditionally, getting data like this requires flying a plane over the area at one point in time, which can be quite costly,” said Yanites. “With this drone, we get on-demand remote sensing that allows us to collect as much high-resolution data as we want to get a better sense of how things are changing over time.”

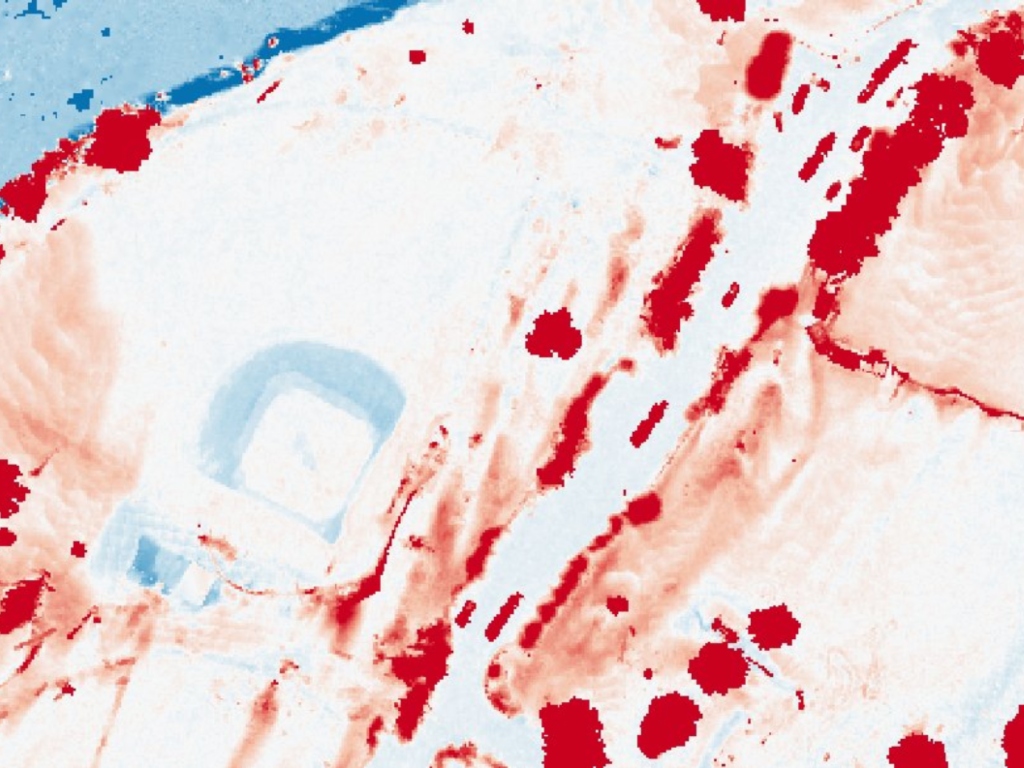

IU researchers started flying over and mapping the flood area around June 1 to look for patterns of erosion and sediment deposits. Lidar-equipped drones shoot 100,000 laser pulses per second to capture fine-scale information about the landscape. Using June’s data as a baseline, the team is continuing to survey the dams throughout July 2021 to monitor how the floodplain and river evolve in the wake of the catastrophe. “For instance,” said Martin, “we used the lidar data to calculate that a local farmer lost nearly 12,000 cubic yards of topsoil across 11 acres of cropland.”

Large dam failures have not been common in the US, but a confluence of factors could change that in the near future. A recent infrastructure report card from the American Society of Civil Engineers gave US dam infrastructure a “D+.” As climate change-induced extreme precipitation events become more frequent in the Midwest, improved understanding of how dam failure affects the local environment and nearby communities will become increasingly important.

“Currently, we don’t have a lot of data on the river and ecosystem responses of dam failures over time,” said Yanites. “Given that the predictions of dam longevity and increasing precipitation suggest failures like this might become more common, it is crucial to monitor the response to better prepare us for future events.”

In addition to the dam monitoring project, EAS researchers are using the drone to pursue other earth sciences research as well. Ongoing studies that depend on lidar technology include investigations of how fallen trees shape forests by exposing large quantities of soil, how rivers change over time, how rivers respond to flooding in the Midwest, and mapping hazards in earthquake-prone landscapes.

“We are taking this drone everywhere we do research,” said Edmonds. “The additional information it provides is invaluable because it improves our ability to see small-scale topographic changes in a way that many people are unable to.”