Indiana has seen a dramatic decline in its wetlands, which in turn affects other aquatic ecosystems and water quality for people. Thirty-seven percent of the watershed where Juday Creek is located was wetlands in 1829, but by 2000, wetlands accounted for less than one percent of the area. With the loss of wetlands, nutrients and sediments were unable to be filtered out, which harmed the aquatic ecosystem and the people that used the water for drinking and irrigation. Wetland losses also increased the flood risk to property and infrastructure in the area.

The loss in wetlands was in part due to Indiana’s drainage law that was enacted in 1889 and has been regularly updated. The drainage law, in general, focuses more on agriculture than protecting aquatic ecosystems. Under the law, Juday Creek was reclassified as a drainage ditch instead of its historic designation as a creek. This distinction resulted in management activities, such as dredging, wood removal, and the mowing of buffer zones that disconnected the creek from its historical channel and allowed excess nutrients and sediment to enter the waterway. Additionally, traditional erosion control measures like riprap were deflecting the problem and pushing the nutrients and sediment further downstream.

After continued management activities and development along the creek, researchers found an abrupt loss of species: the number of fish species declined from six to one. Researchers also noted an 85 to 90 percent reduction in the insect-based food sources in the stream. When the researchers presented the evidence to County officials, the officials started to scale back some of the activities. However, by that point, development in the area made it difficult for those changes to make much of an impact on the ecosystem’s health.

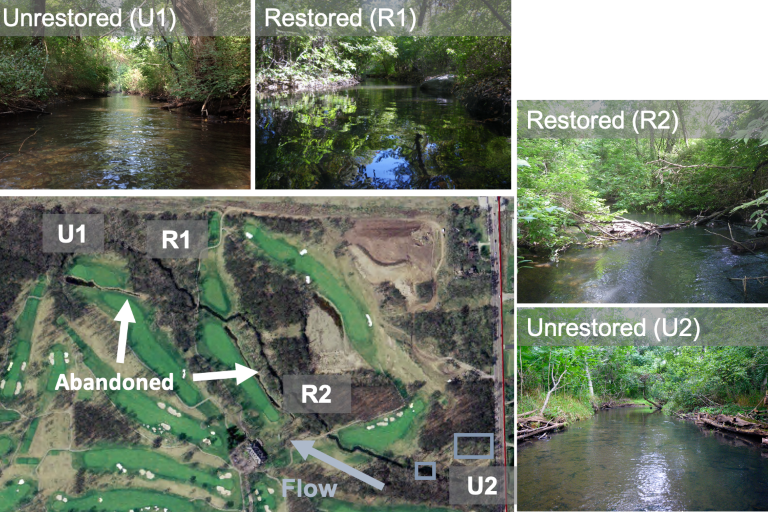

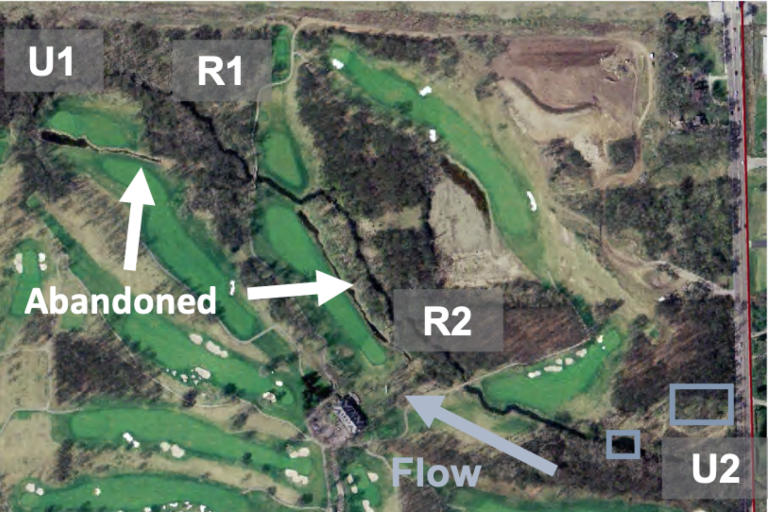

To address the water quality issues in the creek, residents formed the Juday Creek Task Force. The Task Force developed goals and plans to protect the overall watershed. Specific actions included preserving and improving the creek’s populations of brown trout and other species, reducing erosion, establishing buffer strips, reducing mowing of stream side vegetation, and creating a planning process that would address future development, among others. However, once the University announced plans to develop the golf course, and the plans did not consider the aquatic ecosystem in the design, the task force reached out to Notre Dame researchers to determine what they could do to protect the aquatic ecosystem.